A Guide to Nowhere, Part One

The english version of a Japanese serial on rural Nova Scotia

Hi. My label in Japan asked if I would write a series about living in rural Nova Scotia for their online magazine. In case you’d like to practice your Japanese, here’s the translation.

A tractor could be heard and then seen puttering up the road behind a curtain of wet snow. The ocean hadn't frozen and its inlets and marshes were swollen. I was clambering over boxes in the back of a moving truck as the tractor climbed the long rise of the driveway, its tires pressing deep ridges into the mud.

A white-haired man heaved himself out of the cab. He introduced himself in a thick Welsh accent as as John, the owner of the surrounding fields and up until recently this house. His divorce wasn't going well, but he was grateful it brought him some new neighbours. He called me "boy." He was covered in cow shit from the waist down. We had to shout over the wind and the bellow of the tractor's idle. It was technically illegal for him to be talking to me since I'd just arrived from Montréal, and was supposed to be in quarantine for two weeks.

Four days later I rode my bicycle eight kilometres against the wind to buy cigarettes in the village.

The house belonged to my partner Allyson's mother. We had helped her move at the same time as us. Our plan was to go to Prince Edward Island where we had rented an old farmhouse, but the government closed the borders of the province while we waited out a three-day snowstorm in Québec.

I fashioned a desk from a slab of wood and four rubbermaid containers in the unheated basement and tried not to regret my choices.

Ally and I spent the winter searching for a place to live in Nova Scotia, driving hours through snowstorms to look at houses half-sunken into the earth, repeatedly getting turned down by banks because we were self-employed, having every offer usurped by people who had never seen the house in question in person. A lot of rich Ontarians got fleeced.

We ended up moving 30 minutes away from Ally's mother. Her middle of nowhere is called River John and ours is called Pictou. You pronounce it like "PIG TOE." It means "exploding gas" in Mi'kmaq. A massive pulp mill facing the town was decommissioned three years ago but is still in legal bed with the government. Things could get apocalyptic at any moment, hence the low property prices and lack of competition.

A red and white cartoon smokestack across the bay denotes the Abercrombie power plant, which is run on coal and covers everything near it in a fine black dust. Further inland you can hear the incessant buzz of the Scotsburn sawmill. Twenty kilometres to the east is the Michelin tire plant. Across the hill beyond a scattering of windmills is the Stellarton pit mine. It faces a Walmart in New Glasgow, where one literally finds themselves between a rock and a hard place.

This county has 40,000 people spread out over 2800 square kilometres, or 15 people per km/2. Most of them are hiding in the woods, but around 2000 of them are our neighbours. Three quarters of the town is over 55 years old. Ally and I are both turning 30 this November.

If you're reading this, there's a good chance you live in Japan. This has all been translated by my friend Seki. It's kind of like two people are speaking at once.

Seki asked if I'd like to write a series about living in rural Nova Scotia for a Japanese audience. I said yes, with a hunch that there may be more similarities than differences.

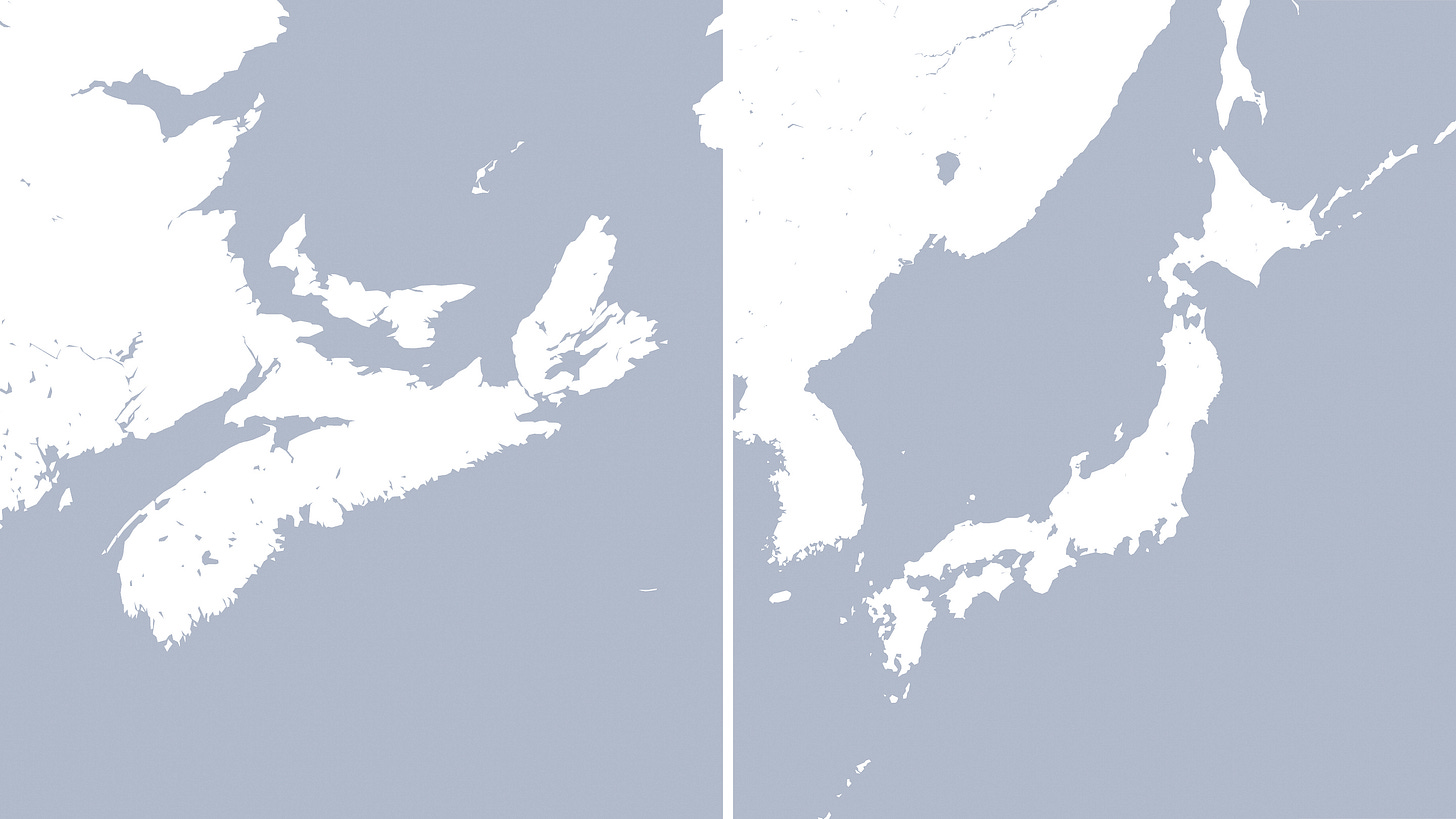

If you check on a map, Japan and Nova Scotia actually look very much alike. Our Cape Breton is your Hokkaido. Tokyo and Halifax are the same urban bellybutton, albeit at massively different scales. The southern shore is warm and sleepy. Your South Korea is our Maine. For the benefit of anyone from New Brunswick reading this, don't ask what our North Korea is.

If I had to choose a Japanese twin for Pictou, I'd say it's Izumozaki: they're both small fishing towns on the north shore facing an island (Pictou Island/Sado), and they're both near a larger community built on forestry and mining (New Glasgow/Niigata). As I follow the highway up the coast I see a familiar constellation of communities: Antigonish/Akita, Port Hawkesbury/Hakodate, and Sydney/Sapporo.

From Montréal to Pictou is 800km as the bird flies, the same distance between Fukuoka and Izumozaki. We left Montréal because I'd read Masanobu Fukuoka's One Straw Revolution and experienced a moment of what the Izumozaki-born Zen poet Ryōkan might have called satori. I envisioned a simple life in the countryside where I grew my own food and never had to look at a computer screen again.

The joke was on me: Allyson and I had a kid, and I'm working on a computer 40+ hours a week to keep the lights on.

But, I have a backyard, and this spring I'm going to plant a garden.

It's the end of March as I write this, and winter is almost over. There will probably be three more months of clouds and rain with one or two snowstorms thrown in. I'm running out of firewood, but another -30°c cold snap is unlikely at this point.

It may not seem like a particularly exciting subject, but weather is the prime topic of conversation in these parts. Whether you're rich or poor, old or young, everyone here gets hit by the same weather.

Hurricane Fiona came through last September to forcibly rearrange the landscape. Some people were without power for months. A friend of mine had the entire roof of their house blown off, so a bunch of us built them a new one. I fixed another friend's fence, and she's going to give me pointers for setting up our garden this spring. Farmer John, from the beginning of this story, lent me a chainsaw and never asked when I'd bring it back.

Everyone helps one another because they know that the weather is indiscriminate. Our neighbour's tree fell through our window, but it could have easily been the other way around. We never talked about it once during the days of cleanup. In these moments the idea of private property fades and a collective ownership emerges—it's just too bad it takes a catastrophe to make it happen.

My friend Marg called and said we're getting snow tonight, so I better go prepare. I'm looking forward to showing you what it's like to live out here in the coming months. Feel free to write back.

Until next time,

IV

wonderful-your a good writer Issac

like the fact that you weave the personal into the comparison

like the ending,bounderies fade due to a storm-who knows,might be permanent

like the person not asking for his chain saw back